Giving good slide presentations

Nicholas LaCara – January 2020 – Boston, maI've had to give countless presentations over the years to audiences of all sizes. I used to be pretty firmly against using slides in presentations, but my position has softened on that over the years. They can be a very effective medium for communicating information when enough forethought is put into them. There's a lot of advice out there about designing good slides, but I wanted to discuss a few lesser discussed pointers about how to give a good presentation using slides.

- On (not) using slides

- The preparation

- Making the slides

- Use consistent design principles throughout

- Structure your presentation, and tell your audience the structure

- Repeat information your audience needs to know

- Don't stuff too much of your presentation into your slides

- Anticipate questions and put the answers at the end

- Consider making a handout

- Giving the presentation

On (not) using slides

My advisor at ucsc was well known for his view on Power Point:

Power Point makes you stupid.

This is put somewhat provocatively, to say the least, but this particular opinion of his was, if I recall correctly, formed from having seen a number of gifted and thoughtful colleagues give flashy, poorly structured and badly paced Power Point presentations. Now, my advisor had a really strong influence on me for many years, even after I started my PhD at UMass, and so for many years I avoided giving any presentations with slides.

My views, though, gave way to necessity as I started giving presentations to larger and more diverse audiences. When I started regularly giving slide presentations, I didn't want Power Point to make me stupid, so I spent a lot of time thinking about what goes into good slide presentations. If I was going to do them, I was going to do them right.

Below, I'll discuss some of my advice for (or, more accurately, thoughts on) how to give a good slide presentation. Whereas a lot of advice online seems to be directed toward how to make good individual slides, my aim here is to get you thinking about the entire slide component as a whole. Because the primary alternative to slides in a lot of cases is the old-school paper handout, for the purposes of this post that's the alternative to which I will compare slides. In a lot of cases, I think that paper is the better way of presenting information, but each medium has its strengths, and they are both worth considering when crafting a presentation. A lot of the advice really boils down to thoughtful forward planning and structuring of the slides themselves.

The preparation

I think one of the main reasons slide presentations can encounter problems is because the presenter does not put enough forethought into how the slides will affect the structure and pacing of their talk. Because the presenter controls how long each slide is on the screen, the audience does not have any control over the speed of the content. Moreover, they cannot look ahead to see where the presentation is going, and they cannot look back if they forgot a previous point. Worse, if someone in the audience is temporarily distracted during one slide and the presentation moves on, they have no way to recover the lost information if the slides are not supplemented with a handout of some sort. Finally, the way slides are presented can have an effect on the presentation, as well. Too often, presenters go through slides monotonously one after the other without giving the audience a clear road map of where they are going.

What I'm saying here is that there are drawbacks to using slides, and these drawbacks should be considered when planning out a presentation of any kind. For a lot of people, using slides is a sort of default way of giving a presentation, but they rarely question whether it is the best way to present the information they want to communicate. Bearing the drawbacks in mind, even if one chooses to use slides, can lead to a great improvement in the slides themselves.

With this in mind, here are some things to take under consideration when planning out your presentation.

Have a reason for using slides

There are, of course, a few really good reasons to use slides.

- They keep people's heads up and looking at you, and that lets you better keep their attention. Handouts are nice because they help the audience to take in information at their own pace, but the counterpoint to that is that they may not be paying attention to you or what you're saying at any given moment.

- That said, make sure people can actually see the graphics when projected.Certain kinds of graphics are just better seen projected, in color. Unless you are willing to shell out for color printing, slides are often the best way to reproduce complex images and data visualizations for your audience, and if you need to show them these things then slides are often the most efficacious choice.

- Slides are more dynamic than handouts. By being able to change the image on the screen, you can draw everybody's attention to the same point. See the image below:

The point here isn't to tell you not to use slides if you can't think of a reason for using them. Rather, it is to suggest you think about how you are using your chosen medium to present information and why you are using it.

The audience matters

While I've used handouts for audiences of up to forty or fifty people, I would be hesitant to go above that number.Another thing to take into consideration is your audience. One of the main factors that got me to start using slides in presentations was having to give lectures to a hundred students at a time – and eventually several hundred! Consider who your audience will be and what they will be like:

- How many people will be viewing the presentation? Slides, by their very nature, need not be distributed to your audience, and consequently they are great for large audiences. People often miss handouts sitting by the entrance or else grab the wrong one, and with large audiences that can lead to several people trying to get a handout after your presentation has begun.

- Will your audience be taking notes? I've seen many talks where a notable part of the question period is lost to questions like 'Can you go back to the slide where you discussed X?', followed up with, 'I'm sorry, I think it was a different slide.' Do everybody a favor: Number your slides, and make the number readable.Handouts can greatly facilitate note-taking since it allows your audience to jot down their thoughts or questions alongside your content. Slides often require them to make a note of what you said or where in the presentation you are along with their note.

- Does your audience expect you to use slides? This falls under the adage 'know your audience'. For instance, if you are giving a presentation to experimental psychologists, I suspect they would see a paper handout as a bit old-fashioned. Don't be afraid to shake things up every once in a while, but if you're looking to make a good impression…

- Do you want them to have something to take away?I got an email last month from an old colleague asking if I could remember a question I asked during a presentation he gave seven or eight months ago. I went to my folder of old handouts, pulled out the one from his talk, and instantly remembered what it was I asked him. Giving your audience a paper handout gives them a physical momento of your presentation which they can refer to in the future. There are circumstances where this can be very useful to your audience. However, if your presentation contains certain sensitive content or information that shouldn't be circulated, a handout is less appropriate.

The venue matters

Finally, it is worth considering what the physical venue will be like. Generally speaking, this is out of your control. You may not even know what the venue will look like ahead of your presentation. But if you do know what you're getting into, there are a few points worth considering:

- Will everybody be able to read your slides or see the screen? This is especially important with large audiences. Sometimes seating is such that even people with reasonably good vision will not be able to read a slide from the back of the room. Perhaps the screen is too small. Sometimes the screen is placed awkwardly off-center in such a way that people on side of the room will not be able to make out what it says. Sometimes a column will be placed so it obstructs the screen for several people. These are usually only inconveniences (people can move), but they are worth bearing in mind.

- Slides are great for presentations over the internet. The first presentation I gave with slides in graduate school was for a seminar that was being co-taught at UMass and Harvard. I could have sent a handout to the professor leading the seminar at Harvard, but I ultimately decided it was simpler to make slides since we had the capability of streaming them over the internet and the audience was going to be looking at a screen anyway.

Making the slides

Once you decide on using slides, you have to make them. There is a lot of well known advice out there (‘Don't put too much content on each slide’, ‘Don't use flashy graphics/fonts’, etc.) and I won't rehearse it all here. Rather, I want to point out some higher-order concerns that I don't see addressed a lot.

Use consistent design principles throughout

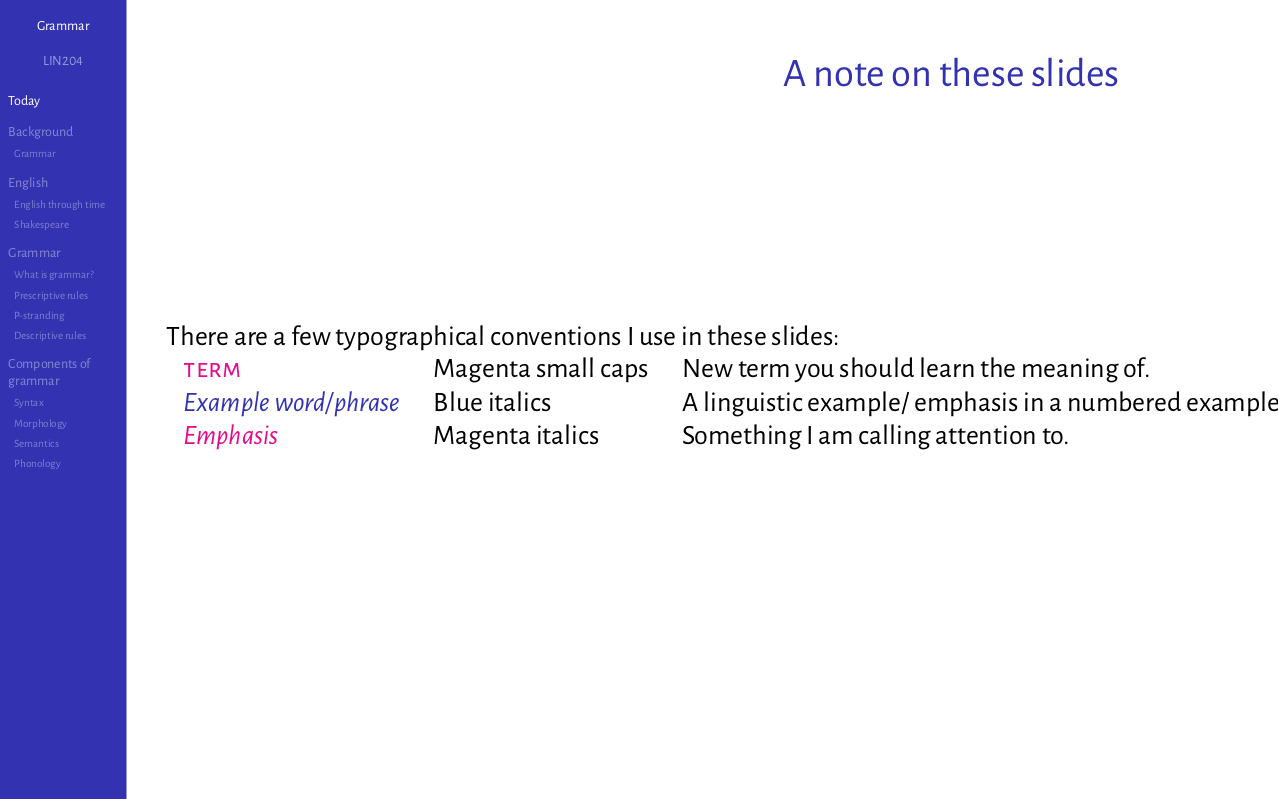

When you start putting content on your slides, try to adhere to some guidelines for how you format the content. Frequent (good) advice on slides recommends against using a variety of typefaces and colors. This helps make your slides look consistent (and not sloppy). Beyond this, though, consider making consistent formatting rules for yourself and following those. It's even possible to introduce these guidelines to your audience, as I did here:

A slide from a lecture on English grammar I gave at the University of Toronto in 2018. Throughout this course, all of my slides maintained the same typographical conventions for terms, examples, and emphasis.

If you're designing with color, don't forget that around five percent of the population is color blind, and red–green color blindness affects nearly 10% of men. That's one in twenty people. If you plan on using colors in your presentation to make any sort of visual distinction, you should avoid using red and green (which are, often, the colors people first choose). For example, in the example slides above you'll see I use blue and magenta, which remain distinct for most color blind people. You should also use some other way of distinguishing text in addition to color, as I do above with italics and small caps.

Structure your presentation, and tell your audience the structure

Beamer (LaTeX-based software for producing slides) provides many layouts that have a visual progress indicator of where the presentation is. As I mentioned above, some poorly delivered slide presentations can feel like the presenter is just monotonously flipping through a series of slides. Because your audience has no way of looking ahead of where you are, it is critical that you tell your audience where you are going ahead of time. Create an outline for your presentation, and include it early in your slides so that people understand the structure of your talk. Remind them from time to time where you are in your discussion. See also the comment above about including slide numbers.You just need to make sure they understand where you are and where you are going.

Repeat information that is important

There is a tendency in slide presentations to show material only once. There's no real need to be so economical, though. Don't hesitate to repeat any information that your audience might need (or even just want) to better understand your point. If you're building an argument that relies on a critical data point from several slides back, show it again. If you make use of an unfamiliar equation, formula, or novel code, your audience will not fault you for giving them another look.

This concern, however, must be balanced against the following concern…

Don't stuff too much of your presentation into your slides

Just as an example: For a two-hour academic lecture, I would usually use around 40 slides. Critical information and explanations went on the slides, but my discussion was necessarily much more verbose. This goes beyond the oft-repeated (and good) advice against putting too much material on any single slide. Remember that you will be there talking alongside your slides. The slides should be a guide for your talk and not a transcript of what you say. This means that you shouldn't feel compelled to put every piece of information you say into the slide component of your presentation. If you need to repeat information (as discussed above), consider whether that information needs to be visually displayed or whether it is better communicated verbally.

That said, every presenter is comfortable with a different level of information on their slides – there's no hard-and-fast rule regarding how much information to include. The point is not to overwhelm or distract the audience, who will be trying to read them while listening to you.

Anticipate questions and put the answers at the end

In the vein of the previous point, you may want to avoid putting every relevant point in the main part of your presentation, especially if they aren't directly related to the main thread of your discussion. However, if your presentation will have a substantial question period at the end, try to anticipate some of the questions you might get and include some slides after the main part of your presentation that answer those questions if the answer is nowhere else in your slides. There are a few reasons to do this: It makes it easier to answer the questions if you already have relevant materials prepared, and from a rhetorical perspective, it makes it look like you've given the topic of your presentation a lot of thought. Preparedness looks good.

Consider making a handout

I should point out that this was possible in large part due to the fact that I was using Beamer rather than Power Point. There are packages for Beamer that greatly facilitate the production of true handouts from slides.I have made a handout to go with slides exactly once (for a presentation in a seminar in graduate school). The handout had the same content as my slides. It was not just a 3 × 2 printed copy of my slides, but an actual letter-sized, bullet-pointed handout. This allowed me to include some footnotes (which should never go on a slide) as well as a full bibliography. My audience was impressed and seemed to like having both.

Creating a handout in addition to slides can be time consuming, and the value may only be marginal. I bring it up only because it is rarely considered despite mitigate many of the issues raised above. I have on occasion seen people provide short handouts with only critical information and citations as supplements to their slides, which helps manage the need to repeat information, allows readers to freely check complicated information, and can allow you to leave more visually complicated material off of your slides.

Giving the presentation

Most standard advice for giving presentations comes here: Come prepared, come on time, relax, and remember you're in control. With luck, you've practiced your presentation at least once if you've had the time, and you have a good sense of how your presentation is structured. There are just a couple things I recommend bearing in mind:

Be comfortable skipping slides

Most good advice for giving presentations will tell you that you should determine ahead of time what material you can skip if you are short on time. An odd behavior I've seen during slide presentations is when people will skip through their slides one-by-one to get to the next sectionAnother advantage of beamer, mentioned in some of the sidenotes above, if that it can automatically provide various forms of section- and sub-section-level navigation so that you don't have to skip a slide at a time., but upon seeing a slide they think is important, they will stop and start talking about it. This is often and issue for a couple reaons:

- If that slide is so important that it needs to be talked about, then the material it's in shouldn't have been deemed skippable.

- Since previous slides have been skipped, the slide that's been stopped on is often robbed of some of its previous context, forcing you to discuss material that you skipped. This can be confusing, as you risk losing your audience who might not follow your discussion.

Have a pdf version of your slides

Once at a conference when a Mac refused to display one of my students' slides, I let her use LibreOffice Impress on my Ubuntu-based laptop to display Power Point slides she made under Windows 10, and it went off without a hitch.Technical difficulties with slides are becoming less and less common, but if you're a Power Point user, it can still happen that the computer in the room you're in just refuses to display your slides the way you thought they'd look. Just in case, it's good to have a pdf version of your slides on hand. Almost every modern computer has a pdf viewer, and your slides should look the same on any computer you have to give your presentation with.

Conclusion

In the end, perhaps the best advice is not just to be prepared, but to prepare thoughtfully. Don't put your slides together at the last minute if you can help it, but instead take some time to think about what the goals of your presentation will be and how you can use your slides a tool to meet those goals. Be mindful of the structure and pacing of your presentation and how you use your slides to control the flow of information.